No. 26, Vol. 3. Vernal Equinox 2014

An Introduction to the Book of Magic, with Instructions for Invoking Spirits, etc.,

ca. 1577-1583, Folger Shakespeare Library MS. V.b.26

by Teresa Burns

Folger Shakespeare Library’s manuscript V.b.26, the Book of Magic with Instructions for Invoking Spirits, etc., is without doubt the most eclectic collection of maledictions, invocations, conjurations, tables of correspondences, lists of offices of spirits, magic squares, magic circles, sigils, illumined swirls, directions for unpleasant animal acts, recipes for fairy potions, unexplained ciphers and drawings of dragons, demons and angels that I’ve ever seen. Every section seems to contain some sort of mystery cloaked in a non-sequitur,  as if challenging lovers of old grimoires to go over each page just one more time, to try to understand this one little section before going on. The Fairy King dares you, it seems to say.

as if challenging lovers of old grimoires to go over each page just one more time, to try to understand this one little section before going on. The Fairy King dares you, it seems to say.

All right, then. Game on.

But for today, a short introduction will have to get things started. We lovers of old manuscripts talk a more daring game than we actually play.

It’s a toss-up whether MS V.b.26 is best known for its pan-European mix of spirits, for using fairy magic within a Goetic structure or simply for the lengthy series of conjurations culminating with one for the Fairy King Oberion at the end of the second section.

Even if a reader has world enough and time to struggle through relatively neat early modern English handwriting and knows enough about Renaissance Hermetic magic to set herself up for what’s in effect a necromantic quest for the philosopher’s stone, that same reader might sense that something is… more than a little odd, the way a thought experiment feels when its different solutions take one in totally different directions. Who put this lengthy document together, one wonders, and why? The final section seems more like a practice session for solving simple ciphers than anything else; could the whole working just be a ruse for something else? Or (more likely), is it that the working itself must be clandestine?

Thought to date from the late 1500s and of unknown origin, the Book of Magic’s 235 handwritten pages have passed through the hands of British antiquarians and occultists ranging from Robert Cross Smith (“Raphael”) to Frederick Hockley. Over time it wound up broken into three separate parts, two of which are rejoined as V.b.26 and one of which remains lost.

The entire manuscript has been digitized and available here for the past several years, so one can freely look through the whole manuscript without having to worry about the wear on a 450 year old text. The manuscript’s provenance and other cataloguing information are also on-line. A more rapidly perusable “book reader view” is also set up for each of the two sections, V.b.26 (1) and V.b.26 (2).[1]

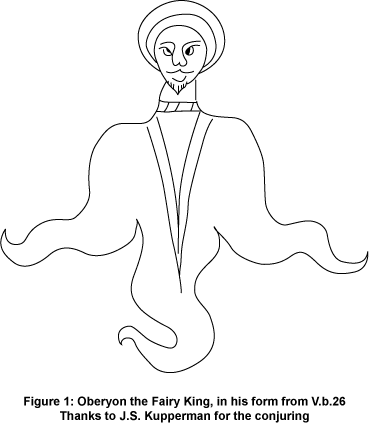

Different parts of the Book of Magic have been copied from the 17th century on. Within the last few years, many of these partial and/or reworked copies have become available in printed form; for instance, two works edited and introduced by David Rankine, The Book of Treasure Spirits, a grimoire of magical conjurations to reveal treasure and catch thieves by invoking spirits, fallen angels, demons and fairies and The Grimoire of Arthur Gauntlet: a 17th century London cunningman’s book of charms, conjurations and prayers[2] both draw upon 17th century copies of sections of V.b.26.

By the 19th century, occultist Frederick Hockley at one point copied a copy of part of V.b.26 (which he called “a Folio Manuscript on Magic & Necromancy Written by John Porter, 1583”) before he became the owner of the original years later.[3] The manuscript had by then been separated into parts, and while Hockley wound up owning the largest section of about 190 pages, it’s almost certain he never saw the first section and what he saw of the final section may have been someone’s copy.

Hockley also worked different parts of this grimoire and many others into his own magical repertoire.[4] Some of his magical papers which have stayed for years in private collections have come out in print recently and at least two show sections drawn in part or in whole from V.b.26.[5] At some point, Fred Hockly also created a handwritten, illustrated manuscript which among other things provides a conjuring of Oberion.[6]An Oberion /Oberon/Auberon/Alberich by any Other Name Might not be the Same

We’ll take a look at Hockley’s Oberion later in this article. First, let’s try to find the context for the one we have in the Book of Magic.

|

|

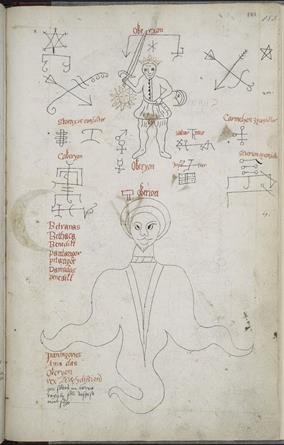

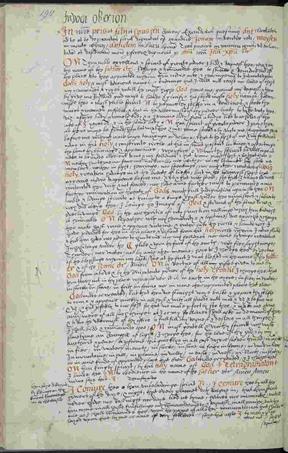

Figure 3: V.b.26 (1), p. 185 and p. 190 © Folger Shakespeare Library used with permission

To start with the most obvious observation, the Book of Magic’s Oberion/Oberyon looks more like a genie than like the Fairy King Oberon of Shakespeare’s Midsummernight’s Dream or the dwarf Auberon of the French medieval romance Huon of Bordeaux or the dwarf Alberich from the Middle High German Nibelungenlied. He’s turbaned and when not floating in the air seems to perfectly command all of the elements with his sword. We might wonder, just in terms of time and place, why he appears this way. Now, for the obvious problem in interpreting any of this: the handwriting which explains how to invoke him is extremely difficult for most of us in the 21st century to read, even if we look at it on-line and zoom in as much as we can…. and that assumes we’ve understood the 189 pages before it. We’re barely going to be able to touch how the Book is structured before this article ends, so much of the exploration will be left to the reader.[7]

Page 80 of the manuscript describes his office thus:

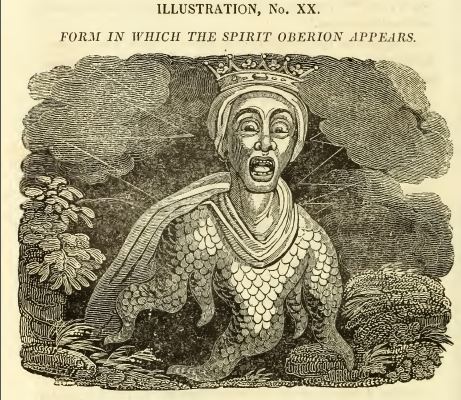

he appeareth like a kinge with a crowne one his heade. he is under the govermente of the [sun] and [moon]. he teacheth a man knowledge in phisicke and he sheweth the nature of stones herbes and trees and of all mettall. he is a great and mighty kinge and he is kinge of the fayries. he causeth a man to be Invissible. he showeth where hiding treseuer is and how to obtain the saime. he telleth of thinges present past and to come: and if he be bounde to a man he will carry or bring treasuer out of the sea. . . |

The Oberion in this manuscript might be thought of as the master alchemist of an age that worshipped power. In the description of his office and in his placement between the Sun and Moon, we also notice the nod to thrice-great Hermes. Oberion’s reputation as a powerful spirit who can show the Operator where to find buried treasure on land and under the sea had already appeared in earlier texts (as do references to him being conjured by a skilled Operator with a magic book, often by being evoked from a crystal or magic mirror). A quick search on-line using “Oberion”, “treasure” and related variant spellings should take readers to several examples from the late 1400s or early 1500s. Oberion’s ability to make the Operator invisible will become the subject of another section we’ll look at in a moment. But first, let’s indulge in some historical gossip.

During the popular early years of Henry VIII’s kingship, when the young King relied so heavily upon Cardinal Thomas Wolsey for advice, it was rumored that Wolsey, the richest and most powerful man in the country besides Henry himself, had Oberion bound to him.

The most oft-repeated story comes from 1529, when a Sir William Stapleton (a “truant monk and unsuccessful magician”[8]) wrote to Cardinal Wolsey to tell him about a group that had tried to conjure Oberion to help them find buried treasure. Stapleton admits that while in the monastery he’d been given a magic book called “Thesaurus Spirituum, and, after that, another called Secreta Secretorum, [and] a little ring, a plate, a circle, and also a sword for the art of digging.” Since treasure hunting without royal license was illegal (and since he’d found no treasure trove himself anyway), Stapleton apparently wanted to inform on others while at the same time seeing if the rumors about Wolsey were true. In his letter, he tells Cardinal Wolsey that the nearby parson of Lesingham “had bound a spirit called Andrew Malchus” and had “called up of late Andrew Malchus, Oberion, and Inchubus.” Stapleton wrote that after they’d conjured up these spirits, Oberion refused to speak. When the parson demanded that the spirit Andrew Malchus tell him why Oberyon refused their command, Andrew Malchus said that was because the Oberion was bound to Cardinal Wolsey.

Stapleton continues with his story for pages, claiming that the plate that they were using to call Oberion was now in the hands of Sir Thomas Moore, another of King Henry VIII’s advisors. . (Apparently the Fairy King didn’t bother with the less than totally rich and powerful.) Stapleton said he wound up in prison, but as soon as he was out, the Duke of Norfolk (Wolsey’s rival, Anne Boleyn’s uncle, and Lord Treasurer of England) wanted him to find out if Cardinal Wolsey had “a spirit;” i.e., if Oberion was still bound to him (which would then presumably explain how Wolsey had gotten so wealthy.)

We’re not told what Cardinal Wolsey’s response to this letter was.

If, as you listen to this story and hear “Andrew Malchus,” you hear it as a variation of “Andromalius,” the goetic spirit who helps to find lost things including hidden treasure, then you’re sliding back into the 16th century context very nicely. By the way, the best contextual introduction to MS Vb26 is still Barbarba Mowat’s 2001 article “Prospero’s Book”,[9] and Mowat points out these same things. If one keeps in mind that Dr. Mowat is setting a context for Shakespearean scholars to understand magic books rather than for western esotericists to understand Fairy Kings, one will find her article a helpful stage-setter, all puns intended.

Mowat is at pains to separate the Oberion/Oberyon of the grimoire from the Oberon/ Auberon/ Alberich of medieval romances and Grail quests, and says that “the Oberion of MS Vb26, though in part Oberon, is also a spirit of another sort with a quite different history.”[10] While those histories overlap, it’s easier to keep them separate when first getting acquainted with the manuscript. On the other hand, if you already know medieval literature and have grown up on the magic of King Solomon, then you know that both the romances and the magical operations are quests (for the Grail, for the philosopher’s stone, for true love, true Kingship, etc.). Maybe then you can draw your own conclusions about Huon of Bordeaux’s Auberon, like the Book of Magic’s Oberion both being from the “mystical east” and appearing foreign.

Conjuring Oberion after conjuring all the other powerful spirits which precede him in the Book of Magic seems pretty clearly an operation likely constructed to help the Operator gain wealth in some form. Yet the final ten pages of prayers and conjurings conclude with the simple exhortation for the Operator to “Then demaund of him [Oberion] what thou wilt.”[11]

Before going any further, it’s really worth the reader’s time to try and see if you can read some of the text yourself. An opening oration occupies the first pages (and remember, V.b.26 starts on page 15 because the first part of the manuscript is missing); by page 17 the first of the colorful calligraphy letters added two hundred years or more later by owner Robert Cross Smith appears, along with a few marks in the margin. Often times, throughout the manuscript, one will see a “W” in the margin one place and a cross in another.

The text is mainly in English with the exception of some Latin words like “Oremus” (“Let us pray”) and magical terms. (On page 17, for instance, the Tetragrammaton is written in Hebrew, but most non-English words are written phonetically in Roman letters.) One may want to try reading a particular section that has already been transcribed and printed in modern type so it’s easier to slowly teach yourself by checking against what’s already been done.[12] For several years different writers have planned to come out with printed editions; perhaps it was a more difficult project than anyone imagined!

In any case, before we reach Oberion or any of the long conjurations at the end, there’s whatever is missing in the first fifteen pages, followed by the writer’s long letter and defense of Catholicism, then over 150 pages of religious exhortation, lists and lists of offices of spirits, maledictions, suffumigations and the days of the week to use them, lists of Greek and Roman and other gods and goddesses and tables of correspondences for different celestial intelligences, lists of helpful plants that can be used to see and control spirits, a series of rather nauseating discussions about how to kill and drain blood from lapwings and swallows for particular spells and how to create particular oils to be used on particular days of the week to see spirits in the air, how to consecrate the Seals and Circles, how to call the spirits, then pages and pages of conjuring and binding spirits.

Occasionally in the margins a later hand will have noted where something correlates to a spirit in a work by Reginald Scot or Agrippa or Peter de Abano, or something will be marked and renumbered. Then the highlight of the work begins: illustrations and conjurings of the spirits Bilgall, Asassiell, Bethalar, Annabaoth, Ascariell, Satan, Baron Bareth, Romulon, and Mosacus. By the time the writer gets to the conjuring of Orobas, the Prince of the Gates of Hell, one suspects that much may be demanded of the Fairy King when he appears.

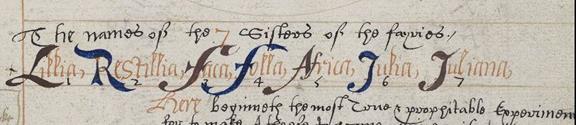

Early on, the Fairy Queen Micob is also listed, and on one of the blank pages in the middle a later owner has noted “Mycob is queen of the fairies, (i.e. Mab).” Queen Mab or Mauve, about whom Mercutio gives a long speech in Romeo and Juliet, is the Irish Queen of the Fairies; her court of seven fairy sisters are “to shewe and teache a man the nature of hearbes and to instruct a man in phisicke. Also they will bringe a man the ringe of Invissibillity.”[13]

Figure 4: V.b.24 p 7: detail of the names of the seven fairy sisters. The colorful lettering was done by Robert Smith, a later owner of the manuscript. © Folger Shakespeare Library used with permission |

The lists of non-fairy spirits doesn’t fit neatly into any previous grimoire I’m aware of. There’s even a note at the beginning of the second section that suggests that the “scribe” didn’t know proper forms of Hebrew, and points out that “on the seals and diagrams the six-pointed Star of David is in almost every case replaced with a cross.”[14] Sotheby’s 2007 listing for the second part of the manuscript said:

This manuscript is not. . .a copy of the Key of Solomon (Clavicula Salomonis), but rather an eclectic and personalized anthology drawing on a range of Solomonic and other sources. Manuscripts of the Clavis Salomonis from the period vary considerably and elements taken from the Solomonic tradition include the use of a sword in ritual magic and the conjuration of elemental spirits. Traces may also be found of the Lemegeton (including the Goetia), and the Liber Juratus. Other spells, such as the ritual eye, seem much more idiosyncratic. Much of the text is set within a Christian framework - in line with reform of the occult arts proposed by John Dee and others. The Trinity and saints are frequently invoked, crosses often replaced stars, and the text is interspersed with Biblical passages (including Peter 5:8 and John 1:1). There are also a signs of an older and darker tradition in the use of blood rituals and, on one occasion, a reversed pentacle.

Curiously, while the Solomonic spirits don’t completely correspond to other grimoires, the Book of Magic’s “seven fairy sisters” seem to have more than an incidental connection to several other manuscripts, including those in Reginald Scot’s 1584 Discoverie of Witchcraft and to the list in another Folger manuscript, Spell to Bind the Seven Sisters of the Fairies to you for ever or X.d..234 (ca. 1600), a one page sheet of spells which Frederika Bain summarizes as “spells to summon, supplicate, control, and copulate with the seven Sisters of the fairies.”[15] If the goal of the Operator in this ritual is most likely to gain wealth, the goal in the four spells transcribed by Bain seems to be to gain a submissive fairy sex slave. Notably, this one page sheet of spells, also viewable on-line, is in a hand very similar to that of Vb.24, and one of the smaller spells

Tracking the names of particular fairy sisters in different texts could show us much about a less-frequently studied part of the western mystery tradition. Bain notes that “Two other spells, in MSS 3824 (1649) and Sloane 1227 (ca. seventeenth century), give as the names of the seven sisters of the fairies to be summoned several that are identical or similar, but none [but X.d. 234] makes any mention of copulation, and they are almost certainly more recent.”[16] That is true enough, though much is left for inference. For instance, one of the smaller spells described in the second section of Vb.24 tells how to "cause a spirit to appear in thy bed chamber."

As the Operator begins invoking celestial energies, it seems fairly clear that most of the time the spirits are summoned into a crystal. (Ascaryell/Ascariell, who appears in Vb.24, is the same spirit summoned in Sloane MS 3848 “to see most excellent & certainlye in a Christall stoune what secret thou wilt.")

By page 139 of the Book of Magic, a group of “Sibilis” appear, so instead of Queen Micob and her court of Lillia, Restillia, Fata, Falla, Africa, Julia, and and Juliana (who elsewhere is called “Venalla,”) we have Julia, Hodelfa, Juafula, Sedamylia, Reaina, Segamex and Delfornia join the “valiant prince” Arthur.

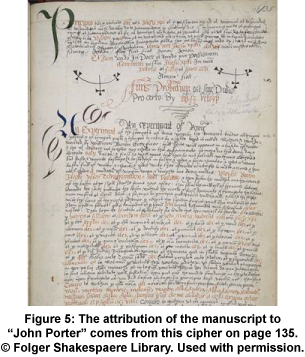

One aspect of the Book of Magic that I’ve so far ignored are the ciphers. Much of the final 19 pages are filled with ciphers—obvious, easy ciphers—but why they are there is anyone’s guess. However, it’s only from a cipher that some later person deduced, perhaps incorrectly, that the manuscript was written by an unknown “John Porter.”

On page 135 (figure 5), notice how a later writer has added colorful calligraphy but also made some notes on the page in pencil. (The red italic letters on this page are in the same hand as most of the rest of the manuscript, but the green “P” and the serpentine flourish next to “An Experiment” were both added later.)

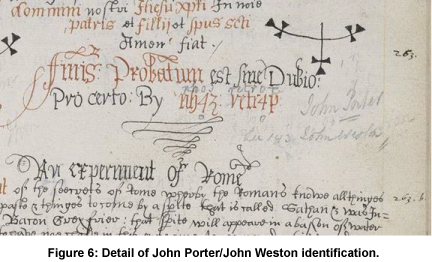

On the Folger site, it’s easy to zoom in on page 135. If one does, one sees that someone has read the red letters “nh4z retr4p” anagrammatically as a simple backwards cipher for “John Porter,” and then for reasons left unexplained, written “John Weston” under “John Porter” to the lower right of the red letters. This seems the only empirical basis for naming the unknown “John Porter” as the original author or even as the original copyist.

If one does zoom in on that cipher, that part of the page, the deduction that John Porter is the writer seems even stranger:

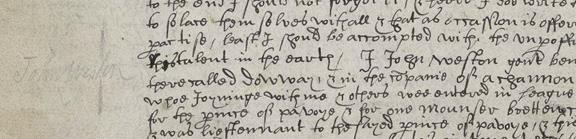

Now, it looks like a close reader, almost certainly Robert Cross Smith, has written that John Porter “equals” John Weston, and next to Weston’s name has written “142,” when is the page number where Weston appears in the text. On page 142 (see below), in the same handwriting, someone has written a vertical line next to the part of the text that says “I Iohn Weston gent.” It’s hard to read that below, but if one looks at this transcription of page 142, at line 43, it should be easier to follow. Similarly, on the transcription one sees many places where the writer refers to a “Mr. W,” and each time, the penciled hand has moved to the margin and written a “W.”

Figure 7: A modern writer pencils "John Weston" into the margins of page 142.

© Folger Shakespeare Library used with permission

If one follows the rather fantastic story told on page 142, it seems that the writer is beginning by telling how to have a spirit vision by taking a lapwing, killing it, letting it turn to worms, making a paste with it and so forth. (I hope the reader has already eaten before reading this section.) This process continues for ten or twelve days more, he claims, and the paste will turn into a worm then into a lapwing then with the blood of that lapwing, one can … well, those who want can read over that on their own. The point is that by line 20, the writer shifts to a story of how he saw this wort of ointment made by a “learned Turk” who was for some time the companion of “Mr. W.”

He continues. When the Turk was in Alexandria, he says, the Sultan of Egypt asked him to reveal how to make this particular ointment, and when the Turk wouldn’t do it, he was ordered to be slain. The Turk wanted to talk with the said “Mr. W.” and so – and here the writer shifts to first person – “we” conferred together. At that point, it seems that the writer is “Mr. W.”

When they are going to depart (Mr. W. to leave, and the Turk to be slain), Mr. W. kisses the Turk, and the Turk gives him a ring so he becomes invisible. Having given the ring, Mr. W. becomes visible and the Sultan’s men seize him. The invisible Turk then announts Mr. W’s eyes, at which time he (Mr. W.) sees a huge number of spirits, and charges them to “minister to me their help.” Then suddenly:

there hapened a greate tempest a greate tempest [sic] & soe greate thvnder & lyghtninge

that the Sarasins which leade me fleed & were soe dispersed, that they leffe me alone

& I seeinge them in such feare that they Ranne awaye, & as men dismayed fleade, then

I fleed to my fellowe the Turcke, & soe he & I wentto his house both speedely & quietly,

from whence the same night wee flead seecrettly & went to wardes Ierusalem

& Lvmbardy, & leavinge our goods behinde vs the which goods were brought vnto vs

afterwardes by the spirrites with mvtch more/

He says that since then, he’s used the ointment many times. (Well, wouldn’t you?) But there are only three people in the world who could make the ointment: him, the Turk, and someone else that he doesn’t name. He does say that the Turk was named Joseph, “both a greate philosopher, & very Riche,” and taught him:

to the end I should not forget it , & heere I doe write the same for Learned men

to solace them selves withall & that as occassion is offered they might put it in

pactise, least I should be accompted with the vnpofftable servant , whoe hidd

his talent in the earth /

Then the writer positively identifies himself, and adds even more onto his already incredible story:

I Iohn Weston gent beinge in thenowaye in a cittie

there called dowway, & in the companie of a channon a very honest & godly man

whoe Ioyninge with me & others wee entered in league & attempted a seecrett worcke

We’re not told what year this is, but “dowway” is probably Douai, France. If John Weston is English and its after 1561 (and if there is any shred of truth to the hallucinatory story), that puts him at the English College in Douai, which was a Catholic seminary founded by William Allen. Between 1577 and 1583, it would have been high treason for Mr. W. to be teaching or studying there. When he says that he and the Chanon attempted a secret work, it sounds like a hint of becoming a spy for the Catholic League.

Of course that doesn’t mean that the story is true. But it does seem that the writer of the manuscript, on this page, wants someone reading it to think it was written by John Weston.

There was a John Weston associated with Renaissance occultism, or several of them, but none of these Westons would have been known at all to a 19th century reader of the manuscript. Whatever is going on here, one suspects this might not have been the safest manuscript to have, unless the person carrying it was himself a spy, and/or not in England.

Let’s take a brief look at what was happening in England during the dates (1577-1583) mentioned in the Book of Magic. Only a few years in the future, 1588, the Spanish Armada would sale to England. What significance might the years 1577-1583 have to English magicians?

In 1577, people across Europe and the British Isles saw the “Great Comet of 1577” in Cassiopeia. Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe was among those who carefully recorded the event. England and the Netherlands formed an alliance that year, and the first seminary priest executed under Elizabeth’s reign, Cuthbert Mayne, was killed. The situation for English Catholics like the author of V.b.26 would get quickly worse. For reasons unknown, in 1577 John Dee started his diary (really notations in an ephemeris). The latter year, 1583, is perhaps best known to occultists as the year that Polish nobleman Albert Łaski came to England, as did Dominican friar Giordano Bruno. Łaski, Philip Sidney, John Florio and others watched Bruno debate with scholars at Oxford, defending Copernicanism and mocking the Aristotelian logic of his hosts. By that fall, John Dee and Edward Kelley had left with Łaski for the continent. The 1577-1588 time period might be best thought of as a huge build-up to war.

The year 1583 is a sort of cut-off point for much tolerance of non-state supported magical activity in England. Works like Reginald Scot’s Discovery of Witchcraft—published in 1584, the year John Dee and Edward Kelly left for Poland England and the year an arch-Puritan, John Whitgift, became Archbishop of Canterbury and chief censor of printed texts—managed to attack highbrow Hermeticism like Dee’s and the charismatic religions more popular among the poor at exactly the same time. Protestant conservatives, most notably Archbishop Whitgift and Sir Christopher Hatton, cracked down on “radical” Protestants (Presbyterians, ironically) who believed in spiritual illumination.

Perhaps the most famous early 16th century grimoire, Cornelius Agrippa’s De Occulta Philosophia, was not really considered objectionable reading early in Elizabeth’s reign, and thus one can find a record of it in places like John Dee’s library as well as several contemporaneous libraries at Oxford and Cambridge. But by the 1580s, while one might already own old compilations like that of Agrippa’s, one might not want to write anything new or at least not write it and have anyone else know about it. Had someone compiled and tried to print the same material after 1584, at the very least the work would have not received ecclesiastic approval (unless it is worded, like Scot’s Discovery of Witchcraft, as an attack, particularly an attack on Catholics). Because of this political climate, it’s no wonder that we don’t know what happened to the Book of Magic from 1583 until someone copied part of it in the 17th century. It was not a very safe manuscript to have, especially given what the writer says on page 142.

To return to the manuscript itself, after “John Weston gent” finishes telling his story about the magic ring, we’re treated to more pages of conjurations of spirits including Bilgall, Asassiell, Bethalar, Annabath, Ascariell, Satan, Baron Beryth, Romulon, Mosacus and of course, Oberion. Each of these have antecedents, just as the list of seven sisters and the name of the Fairy Queen can be found elsewhere, or names similar can be found. What is most unusual—other than that the Book survived at all—is the lengthy collection of spirits that at first seem like a mish-mash of many traditions.

Given the role of angelic magic throughout the piece, one can’t help but wonder if this “John Weston” is somehow associated with the Westons who became Edward Kelley’s step-family. There are a few problems with jumping to that conclusion, though. First of all, the story told on page 142 might strike some people—most people?—as more than just slightly unbelievable. Second, who would this “John Weston” be? Edward Kelley’s step-son John Francis Weston, who grew up in Bohemia and briefly attended the Catholic Clementium school in Prague, was likely Catholic for much of his life… but he wasn’t born yet in 1577. Could it be his father, who was likely also named “John Weston ”? No, that person died in 1582 (which is how Kelley was able to marry his widow).

Dr. John Dee also happened to have a business partner named John Weston for a time, or at least was involved in a business venture with someone named John Weston who could not have been either Edward Kelley’s step-son or Kelley’s wife’s deceased husband. But that John Weston also is dead before 1583.

More speculating about John Porter or John Weston will have to wait for another day. Let’s take a quick survey of who owned the two extant parts of the Book of Magic between the 1580s and the dates when each section was purchased by the Folger Shakespeare library.

From the Sixteenth Century to the Twenty-First…

As mentioned, the manuscript in the Folger Shakespeare library is missing the first 14 pages, and the remaining 220 pages were once divided into two parts. Much more is known about the first, longer section.[17] Early owner Robert Cross Smith (aka “Raphael”) wrote his initials and a date ("R.C.S., 1822") on page 15, which suggests that even by the time that Smith owned the book in 1822 the first 14 pages were missing. Much of what we know about the history of the largest part of the manuscript—the 205 pages listed in the Folger catalog as V.b.26 (1) —comes from notes written down by a later owner, Frederick Hockley, over 250 years after the original was written.

If one cares to dig through the truly fascinating history of V.b.26 (1), one learns that Hockley copied part of the second section of the magic book many, many years before he owned it. Moreover, what he copied was, as noted earlier, itself a copy made by a man named John Palmer, which either Hockley or Palmer or someone else called “a Folio Manuscript on Magic & Necromancy Written by John Porter, 1583.”

We have no way of knowing if either of these men also “inherited” a story about where the manuscript came from or who created it, or who located the cipher on page 135. We’ve seen how one owner of the manuscript, almost certainly Smith, went through much of V.b.26 (1) with a pencil. It’s this modern hand that locates Porter’s name as an anagram, and who writes “W” in the margins when John Weston identifies himself. That hand has also sketched out some planned calligraphic touches that were never finished, and we do know that the colorful letters on some pages were added in by Smith, just as we know E.H.W. Meyerstein added in the fairy poem at the end.

That part of the Book of Magic, the 205 pages of V.b.26 (1), was acquired by the Folger Shakespeare Library from Day’s (Booksellers) Ltd. in 1958, and then “reunited” with the final section in 2007. An article on the Folger site describes the “magic” that brought two of the three pieces of the Book of Magic back together again. The museum’s curator of manuscripts, Heather Wolfe, apparently glanced at the cover of a Sotheby’s auction catalog, and as the Folger article reports:

[The cover] featured the image of a late-16th-century manuscript page, and she thought it had a familiar look. The Sotheby’s page was one leaf of a grimoire, a book of magic spells and conjurations. Heather noticed, in the upper left corner, the pencil notation 206. She immediately went to the Folger manuscript archives and pulled out Folger Ms. V.b.26, a grimoire in our collection, and noted with mounting excitement that its last leaf was numbered 205. As she compared the handwriting in V.b.26 with that of the Sotheby’s image, it became evident that the two manuscripts had once been part of the same book.[18]

Within only a couple years of purchasing the final section of Ms. V.b.26, the Folger Shakespeare Library had made all of the pages available on-line. Since then, the fun of trying to figure out more about V.b.26 has really begun.

Before concluding this introduction to the Book of Magic, I’d like to take one more swing back through the nineteenth century.

By sometime in the mid to late 1800s, Frederick Hockley, the last occultist to own the Book of Magic before it wound up in the Folger, produced his own hand-drawn manuscript which included an invocation to Oberion. Dan Harms, who has produced a modern facsimile of that manuscript, notes that it might “serve as a coda to the collaborations of two major figures of the occult world, John Denley (1764-1842) and Frederick Hockley.”[19]

In the early 1800s, John Denley’s London bookshop on 13 Catherine Street near Covent Garden was a center of British occultism, and Fred Hockley apparently worked there from his teens on, occasionally hand-producing works for Denley’s patrons and transcribing manuscripts. Many who study Hockley’s manuscripts notice Hockley’s liberal use of writing and techniques from Frances Barrett’s The Magus, and that’s no surprise, given that Frances Barrett was a patron of John Denley’s bookstore and that Hockley used the engraving plates purchased by Denley when he (Hockley) produced the 1875 edition of The Magus.

Other patrons of Denley’s shop included Edward Bulwer-Lytton, whose Rosicrucian novel Zanoni is a treasure-trove of esoterica and dark-and-stormy-night sentences; Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge; and members of the Mercurii, a secret magical society whose members included several apparent owners of parts of V.b.26.: Robert Cross Smith (“Raphael”), John Palmer (“Zadkiel” until the death of Smith, when he became “Raphael”), and George Graham. Celebrated miniaturist painter Richard Cosway (1742-1821), the earliest known owner of V.b.26, was also likely a member of the Mercurii.[20]

Apparently John Denley bought the manuscript from Cosway on behalf of Greene; from Greene it passed to Smith, copies were made by Palmer then Hockley copied Palmer’s copy before winding up with part of the manuscript himself.[21] But all of these men knew each other for many years, and from somewhere among this group came the history of the manuscript that Hockley wrote down in the private manuscript which was recently edited by Colin Campbell and printed by Teitan Press. I’ll return to that manuscript, Hockley’s copy of Palmer’s “Folio … on Magic & Necromancy Written by John Porter, 1583,” in a moment.

No one knows where or from whom Richard Cosway obtained the Book of Magic. Considering the miniaturist’s eventful life, he could have as easily bought it on the European continent as in England. For that matter, given Thomas Jefferson’s famous love affair with Richard Cosway’s wife Maria (who Jefferson knew in Paris in the 1786 while serving as ambassador to France), the Book of Magic could have wound up in the colonial U.S. and been transported to Paris by Jefferson and sold to Cosway.

That last suggestion is only meant in fun: the point is that we have no idea who owned the Book of Magic before Cosway, but we might suspect that there was a particular history that Cosway and the younger Mercurii were interested in, because both parts of the manuscript stayed with a member of this group for years.

If that history concerned someone named Weston or Porter, there’s not much likelihood that any of the Mercurii would know anything about them unless they connected to some other occultists that the Mercurii cared about. Fred Hockley, the youngest of the group, was particularly interested in scrying. He was interested in John Dee’s Enochian materials, (Most readers will know already that the original Golden Dawn’s Enochian materials most likely came from Frederick Hockley via Kenneth MacKenzie; by now it should not surprise us that Hockley obtained many of those materials from John Denley, R.C. Smith, and John Cosway.

While there is good reason to believe that some of the Enochian materials were experimented with in London during the century before the Mercurii,[22] I have yet to see such a history of connections with the Book of Magic. Most assume that the Book of Magic originated in England, but all we really know is that whoever wrote it could write in English with a neat Elizabethan secretary hand that (to this reader) shows some characteristics of Welsh influence.

Incidentally, one finds this illustration of Oberion in R.C. Smith’s Astrologer of the 19th Century just before instructions to “Invoke or Raise the Spirit of Oberion:”

Figure 8: Oberion in Astrologer of the 19th Century

The conjuration which follows is attributed to “an ancient MS. in the possession of ‘Raphael’.”

(That “ancient manuscript” was doubtlessly the Book of Magic ! )

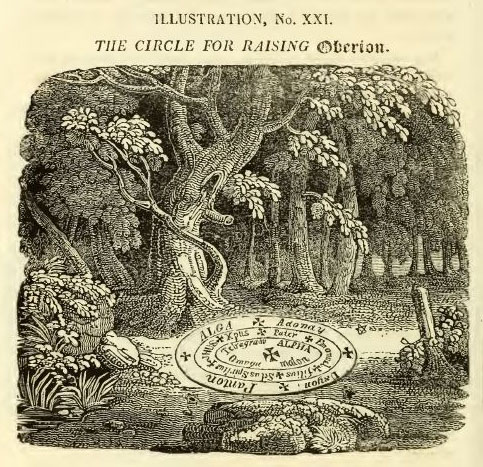

It’s hard to know whether any of the Mercurii used the Book of Magic as practitioners, but not hard at all to tell that Smith didn’t expect his readers to. Smith’s magic circle didn’t come from the same “ancient manuscript” at all:

Figure 9: Oberion's Circle, 19th Century

When the author began reading through the Book of Magic a number of years ago, I was sure that if any of the Mercurii had tried to invoke Oberion, it would have been Frederick Hockley. After all, Hockley was immersed in the work of John Dee and Edward Kelley, collected Enochian material, and had spent hours and hours conjuring spirits with his teen-aged scryer, Emma Louisa Leigh.

I’m less and less inclined to think that’s the case unless it was a Rite he tried before R.C. Smith died in 1832. For one thing, if one takes a look at the drawing of Oberion in Hockley’s handwritten, multi-colored manuscript produced for Denley, one notices that it’s almost exactly the same drawing as Figure 8 above, just more dramatically colored in. In Hockley’s version, Oberion appears ghostly white instead of dark skinned and his clothing has been colored so he appears to have a green gown and purple cape, but otherwise it’s just the same basic image, colored in.

By 1858, when Emma Louisa Leigh died, Hockley had all but stopped copying old manuscripts, and began writing about his work with Emma. His spirit contacts generally involved contacting Emma.[23] Though Hockley lived until 1885, the other Mercurii were dead, and it seems that at this point in his life he would have not likely have spent time correcting a mistaken identification he or John Palmer had made on a manuscript decades before.

For another half century, the Book of Magic, with Instructions for Invoking Spirits, etc., would quietly wind up in semi-storage.

Now, once again, the Fairy King has started to awaken. Maybe in the next few years he’ll tell us what he knows.

Notes

2. David Rankine, (London: Avalonia Press, 2009, 2011). The Book of Treasure Spirits’ cover announces it as a “a partial transcription of Sloane MS 3824, dated 1649, containing material originally bound together with part of Sloane MS 3825, including a conjuration of the spirit Birto said to have been performed at the request of Edward IV, King of England,” while The Grimoire of Arthur Gauntlet is a transcription of Sloan manuscript 3851.

3. Frederick Hockley, as edited by Colin Campbell in A Book of the Offices of Spirits (York Beach, ME: Teitan Press, 2011), xviii.

4. For a discussion of how one of Hockley’s copies mixes from a variety of sources, see Alan Thorogood’s Addendum and Silens Manus’ introduction to Abraham the Jew on Magic Talismans by Frederick Hockley after a work of Frances Barrett (York Beach, ME: Teitan Press, 2011), then note in #5 below how Hockley does the same thing with V.b.26.

5. I’ve mentioned these in more detail in a review here (http://www.jwmt.org/v3n23/hockley_review.html) but they include Hockley as edited by Campbell, op. cit.; Silens Manus, Occult Spells, (York Beach, ME: Teitan Press, 2009)with on-line Addenda et Corrigenda by Alan Thorogood.

6. Frederick Hockley, (scribe and artist) Experimentum, Potens Magna, with an introduction by Dan Harms, (Society of Esoteric Endeavour 2012). Harms notes that this carefully presented, hadwritten, multicolored work may well have been for a special client of Denley’s, and seems “to have been assembled for a collector rather than a practicioner” (1-2).

7. For any readers who are interested, I’d love to continue this conversation, which will continue on my blog until I get tired of it. Until one gets the hang of reading early modern writing—and that is an acquired talent that takes a fair amount of time—it’s a good idea to check against the transcriptions others have done. This is where the many copies of copies that have floated around come in handy. Rankine’s Arthur Gauntlet has a similar invocation with only a few words changed (which is as it should be, since he’s transcribed a copy made less than 100 years after the original.) Working with this manuscript is much easier than with most, so I’ll leave that project to the reader except for a few suggestions in the notes below.

8. Katharine Briggs, An Anatomy of Puc: An Examination of Fairy Belief Among Shakespeare and his Contemporaries (London: Routledge, Keagan Paul, 1959), 114. The lengthy letter written by Stapleton to Wolsey is in Brigg’s appendix, 255-261.

9. Barbara A. Mowat, “Prospero’s Book,” Shakespeare Quarterly volume 42 number 1, spring 2001, 1-33.

12. The writing is a plain secretary hand from the time period with some italic words written in red. It may take some time and eye strain to get used to some of the archaisms. Remember that “i” and “y” are interchangeable during this time periods (hence Oberyon/Oberon) as are “i” and “j” (iohn/john) and “u” and “v” (euer/ever). Long “s” will look like and “f” except an “f;” will have a cross on it, and so forth. A “th” will be written as a thorn (Þ) which in this manuscript will look more like a looped “y.” The writer writes “&” for “and” almost exclusively.

If you spend much time doing this sort of thing (and it does take a lot of time), you may want to use some of the paleography resources that are on-line. If you’d like to read of another scholar’s adventures in transcribing early modern English, Sienna Latham will take you through her transcription of V.b.26 page 55 here.

15. Frederika Bain, “The Binding of the Fairy: Four Spells,” in Preternature, vol. 1 no. 2 (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvanis State University Press, 2012).

17. To recap: V.b.26 is the entire manuscript as currently catalogued by the Folger, two long-separated parts of an entire old text which were rejoined by the 2007 purchase described above. Of the two manuscripts comprising V.b.26, the first-- V.b.26 (1)-- is by far the longer manuscript: 205 pages, of which the first 14 are missing. R.C. Smith (1795-1832) owned both fragments; Frederick Hockley (1808-1885) owned V.b.26 (1). The second manuscript, V.b.26 (2), adds an additional 29 pages, but it is not clear whether these were ever in Hockley’s possession. However, as Alan Thorogood points out in his notes to Occult Spells (op. cit.) some of Hockley’s papers seem to come almost directly from V.b.26 (2), so we know that Hockley either had the second part or the manuscript or a copy of parts of it. V.b.26 (1) seems to have gone from Smith to Hockley to E.H.W. Meyerstein (1889-1952) to Southby’s to the Folger library; V.b.26 (2) went from Smith to an intermediate owner to Robert Lenkiewicz (1941-2002) before being purchased by the Folger.

19. Dan Harms, introduction, in Frederick Hockley’s Experimentum, Potens Magna. (Society of Esoteric Endeavour 2012)

21. For further discussion of this, see Campbell op. cit. and Thorogood op. cit. Hockley apparently copied an older copy that John Palmer, had made in 1832. Palmer, a chemist, astrologer and friend of R.C. Smith, would have likely made his copy from Smith’s manuscript, since Smith seems to have had it from 1822 on. Fortunately Fred Hockley wrote down the known chronology of the manuscript that he was copying a part of a copy of. According to Colin Campbell’s recounting of Hockley’s chronology, the Book of Magic “disappeared for some 200 years, only to re-emerge in the possession of artist and libertine Richard Cosway (1742-1821),” then was purchased by London bookseller John Denley (1764-1842), then by George Graham (1784-1860?) “on behalf of a small occult fraternity, …‘The Society of the Mercurii,” which later included Smith then Palmer. Hockley, the youngest of the group and the transcriber and producer of many manuscripts, would wind up in the position of inheritor and preserver of a particular occult tradition..

22. For more on this, see Alan Thorogood’s recent research in the introduction to Dr. Rudd’s Nine Hierarchies of Angels (York Beach, ME: Teitan Press, 2013). Thorogood’s research showed that this Enochian material came to Hockley via Cosway, and he also casts some much-needed light on odd “Dr. Rudd” stories spun by copyist Peter Smart. Smart appears to have been an older and somewhat removed relative of Cosway’s fellow miniaturist, John Smart